Britannia the People’s Playground

Where did working people go to escape it all in the early 1900s?

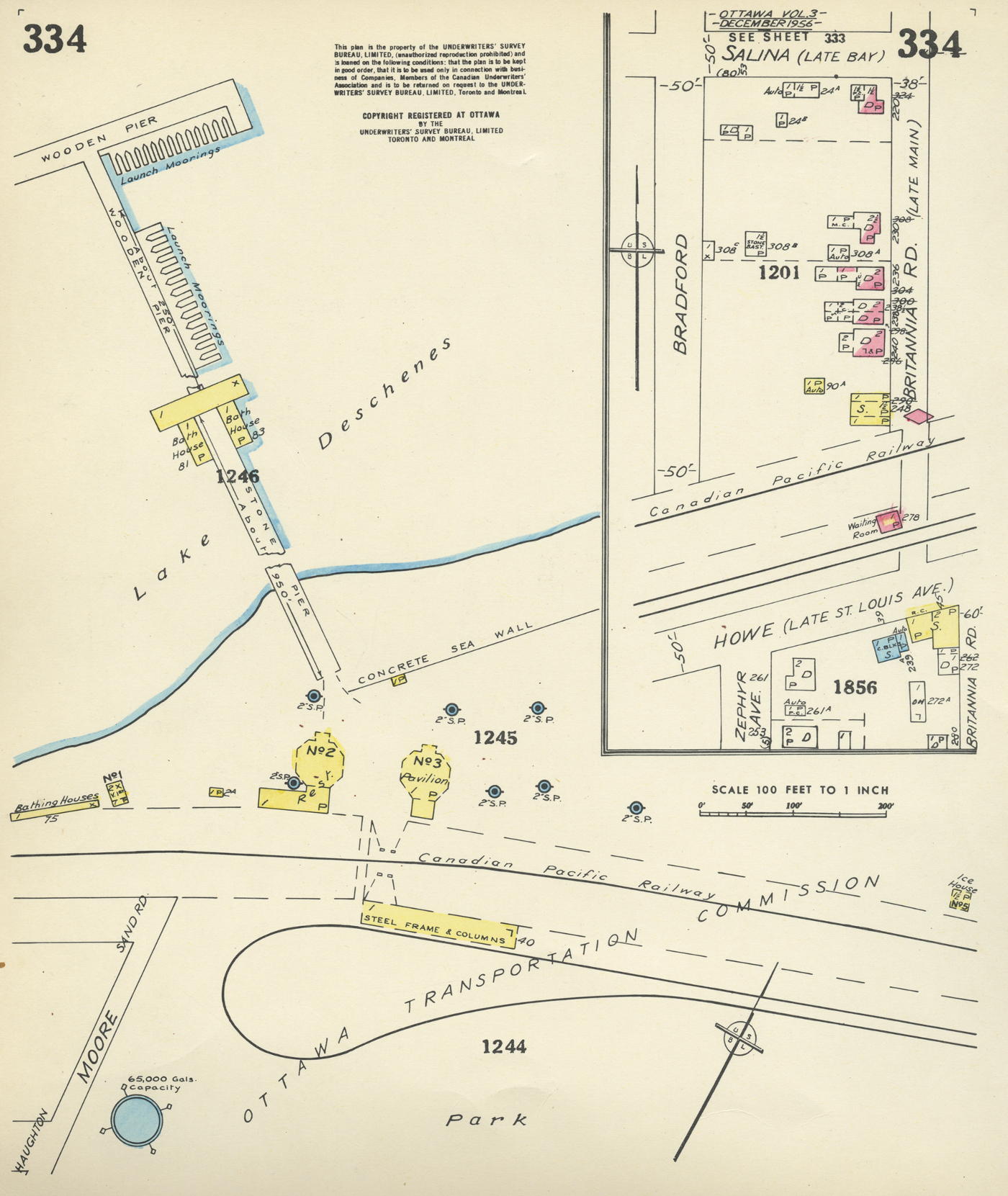

Before there was the internet, television, radio, and even before the “movies,” working people turned to “Trolley Company Amusement Parks” for their fun, entertainment, and recreation. For a five-cent fare, they could head west on the streetcar to Britannia Park. Located outside the city in Nepean Township, the park offered beaches, picnics, rides, music, and dancing. Britannia Park was also used for recreation and sporting activities such as swimming, boating, and rowing. There was even a 1,000-foot pier extending out into Lake Deschenes.

Britannia Park was one of the first amusement parks in Canada and well known across the Eastern seaboard of North America. The park was opened in 1900 and its heyday lasted into the 1920s. It continues to this day as a major recreational destination in the City of Ottawa.

Britannia Background

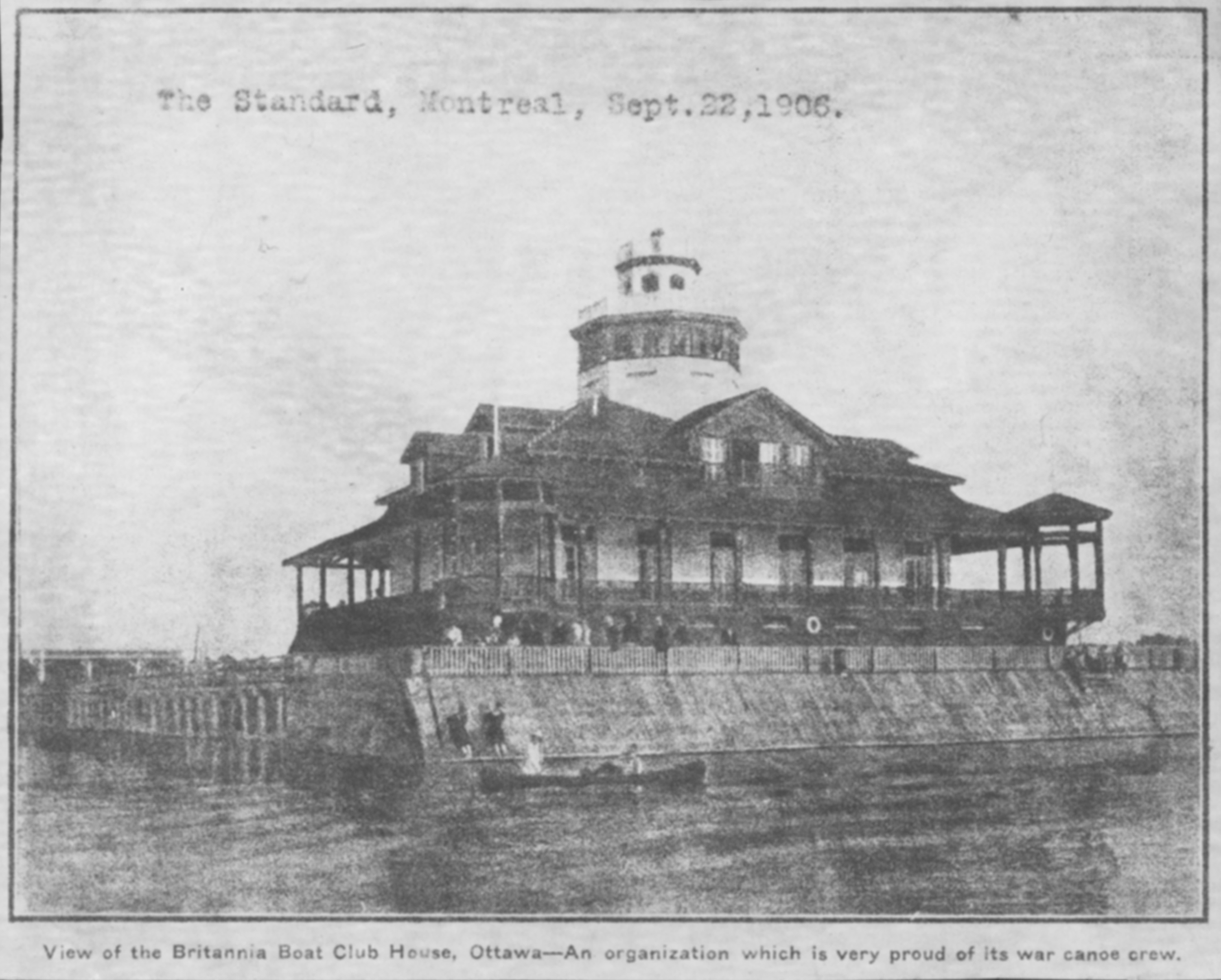

In the early 20th century, Britannia Park was one of Ottawa’s greatest attractions. There was something for everyone: picnics, concerts, swimming, boating, evening dances. Like New York’s iconic Coney Island, this was a place for entertainment and spectacle, especially for families escaping the congestion of industrial Ottawa’s working class neighborhoods. For forty years, Britannia was the Peoples’ Playground.

A Destination

Federal public parks in Ottawa were genteel garden landscapes geared toward passive uses such as strolling. In such parks, baseball, a popular working class activity, was discouraged because it was too unruly. Britannia offered an enticing, if commercial, alternative.

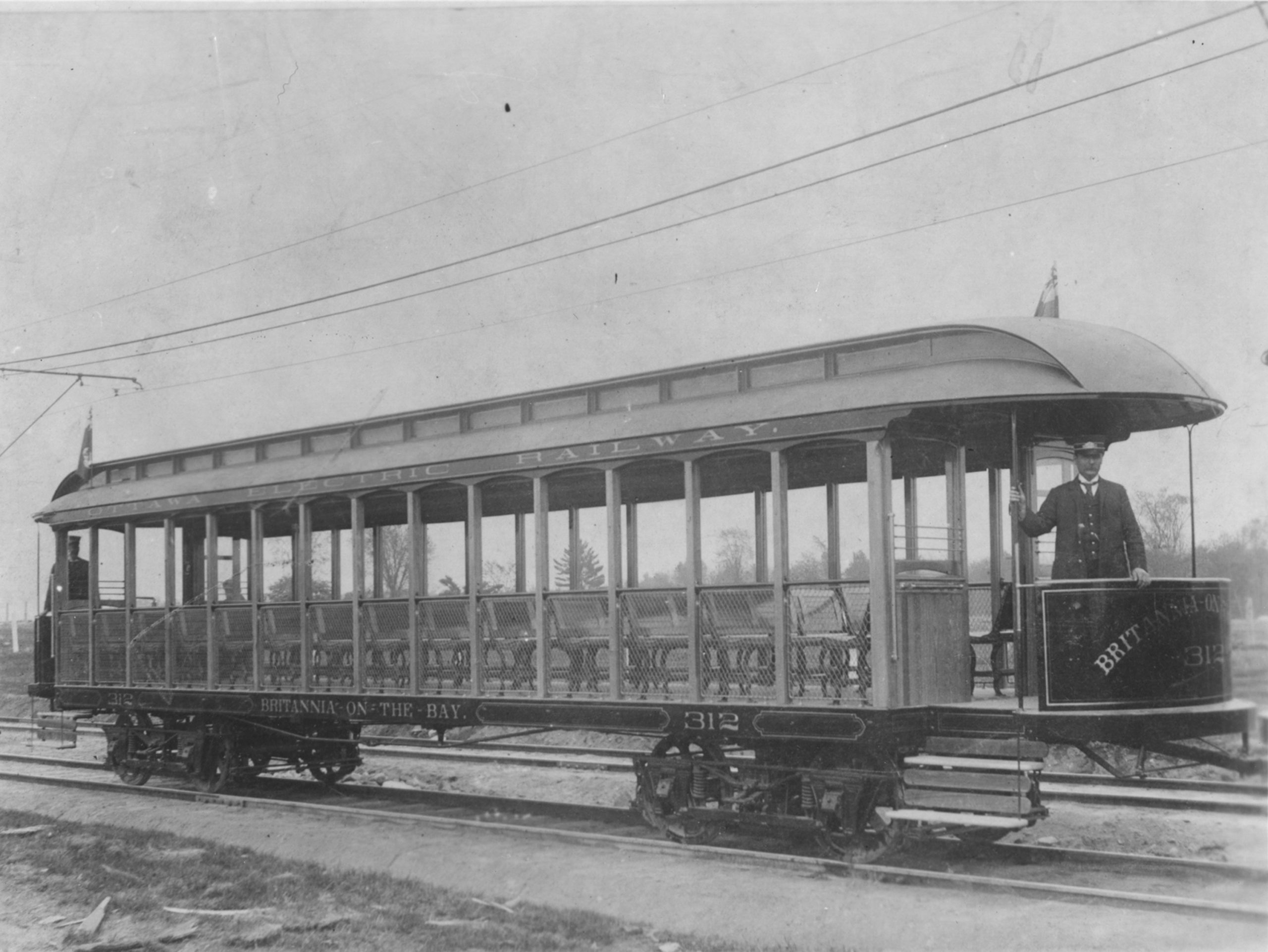

The Trip

Britannia was a trolley park at the western end of Ottawa’s streetcar line. For a 5-cent fare, urban Ottawans could ride the Britannia line into the countryside along Richmond Road. The trip itself was an attraction: an escape from everyday life… for a price.

The Electric Octopus

When Britannia opened in 1900, it was not a public park but the latest addition to a business empire. Likened to an octopus with far-reaching tentacles, Ahearn & Soper owned Ottawa Light, Heat & Power, the electric streetcars, the streetcar factory, and a company that sold land along the line for housing developments and cottage communities. Ahearn & Soper also owned the companies that both manufactured the streetcars and powered them. They profited from daytrippers, commuter fares, and land sales, as well as concessions and auditorium fees from the park.

Growth towards the west

Construction of the OERC Britannia line allowed Ahearn & Soper to develop the western suburbs along the tracks. The seasonal park Britannia and its long tram line functioned at a loss, but as of its creation, the Ahearn & Soper company planned, in collaboration with Ottawa Land Association, to develop suburban communities along the line. The company played a leading role in the development of communities such as Hintonburg for the working class and Britannia Village and Westboro for the middle class. After all, these people would make the shuttle to Ottawa each day.

Drawing them in

Before unions succeeded in winning the weekend, most people worked five and a half days a week. Sunday afternoons were for recreation, but few venues were open. Through their political clout, Ahearn & Soper operated Sunday streetcars, allowing paying customers access to Britannia’s green space for picnics, a swim, and entertainment.

Repeat customers

The Ottawa Electric Railway subsidized annual “Little Folks” excursions – a free streetcar ride and ice cream – to lure the families of the poor back to the park as paying customers.

Britannia’s Golden Years

The first decades of the 20th century were the golden years for Britannia. Riders looked forward to the merry-go-round, auditorium, and baseball diamonds. Band concerts and sing-alongs were common in the afternoons, and the dance hall drew in the evening crowds.

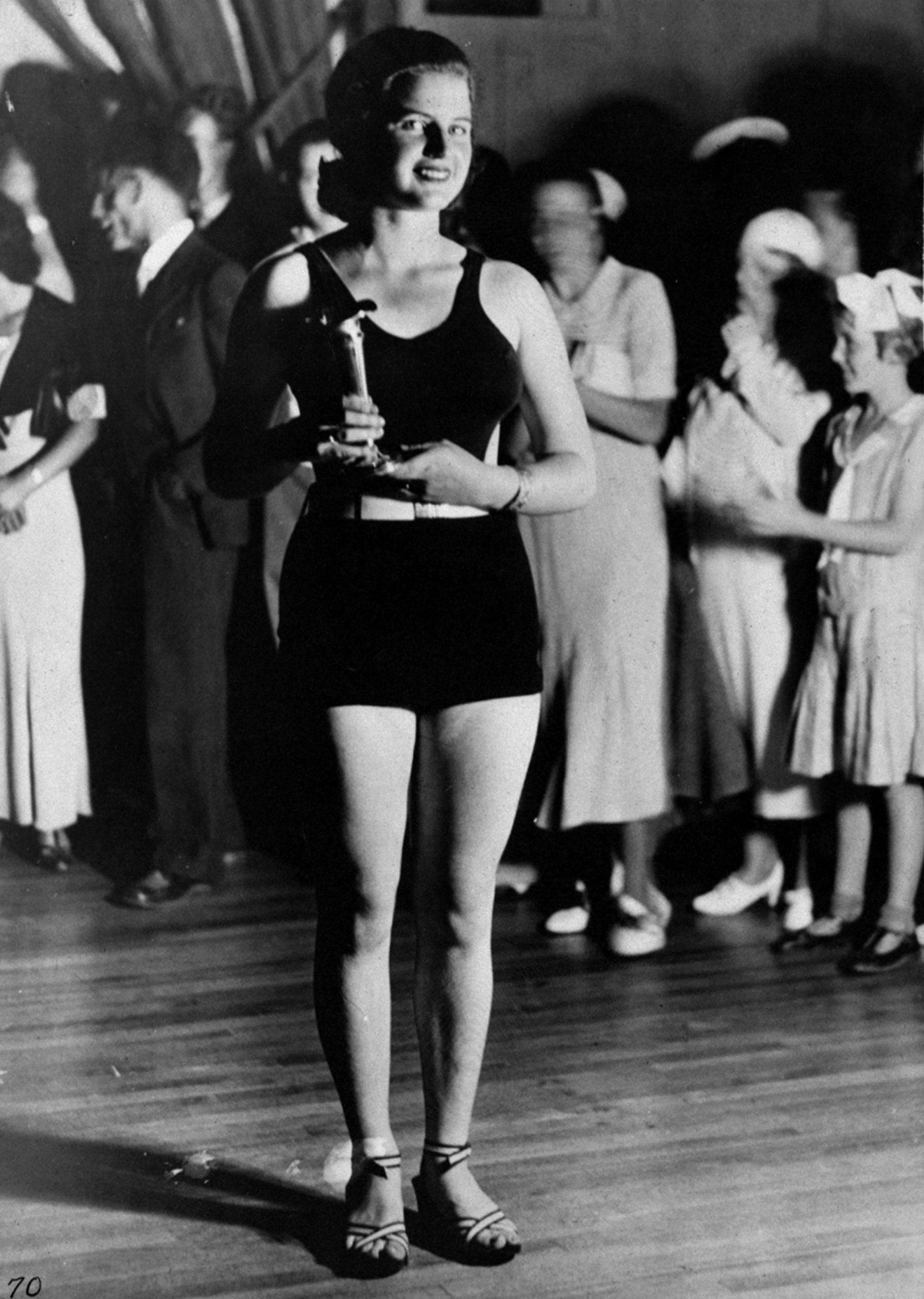

On the Water

Britannia was Ottawa’s first public swimming area, and the shallow water made it ideal for children. The park’s early popularity meant that within the first year, twenty-five new changing rooms were needed to supplement the original forty. Tempted by the beach, visitors who had neglected to bring a swim suit often swam in their regular clothes or baseball uniforms.

Postcards

Private parks like Britannia used souvenir postcards as cheap advertising. Iconic sights such as the pier or boat house became famous around the country.

Lakeside Gardens

The invention of the automobile, the First World War, and the burning of the G.B. Greene dealt a blow to Britannia. Movies and radio, social effects of the Great Depression, and the Second World War, contributed to the trolley park’s decline. In 1948, the City of Ottawa purchased the streetcar company and thus acquired the park. Charlotte Whitton wanted to sell the park land for development, but after a popular campaign, Britannia became a public park in 1951.

Engaging the Community

In a bid to increase visitorship, Britannia Park offered more features to draw people to the West End including moving pictures, concerts, and a miniature train. Evening dances featuring popular bands were a special draw three times a week in summer. Many Ottawans can recall visiting the Lakeside Gardens’ dance pavilion.

The People’s Playground

Britannia Park in its heyday is a rare Canadian example of one company controlling the entire visitor experience, from the trolley ride to the activities within the park. However, it could not have survived without working people choosing a daylong escape from the city. Britannia Park’s beloved status today is evidence of its historic value and continuing importance to the community of Ottawa.

About the Exhibit

The WHM’s exhibition, “Britannia: The People’s Playground,” looks at the history of this Ottawa landmark from a workers’ perspective. This presentation comes in three forms: a virtual gallery on the website, a small travelling display with bilingual panels suitable for display in a museum, gallery, school, college or university, workplace, union, or community centre, and a permanent installation at the Ron Kolbus Lakeside Centre.

A bilingual web site presents the exhibition material on-line and makes it accessible to a wider audience. The museum’s future plans include outdoor interpretation involving QR codes.

If you or members of your family used to visit Britannia Park, we’d be interested in hearing your stories. Please contact the Exhibits and Education committee. If you would like to have the exhibit displayed in your institution, please contact us for more information.

Financing

The Workers’ History Museum acknowledges the generous support we received for this exhibit from:

- Canada Summer Jobs (part of the Government of Canada’s Youth Employment Strategy)

- City of Ottawa

Ottawa’s Electric Railway

Did you know that 100 years ago, Ottawa had a fleet of electric streetcars? The Ottawa Electric Railway Company’s line to Britannia Park made it an inexpensive destination for the working people of Ottawa.

The electric streetcars stopped running in 1959, but Streetcar 696 is now being lovingly restored at the OC Transpo garages. The Workers’ History Museum talked to Bruce Dudley, a former streetcar operator, about his memories of the service.