A SUGAR WORKER’S CEMETERY IN FAR-OFF KAUAI

by Paul Harrison, WHM Photographer and Image Archivist

In my travels, camera in hand, I am alert for opportunities to explore historical sites, and my connection with the Workers’ History Museum makes me particularly eager to identify historic places of work. Rarely, however, does a location so apropos to that theme come to hand as it did this past February on Kauai, one of the islands in the Hawaiian chain. On the south coast is Port Allen, once the primary shipping port for the Island’s sugar industry, and still the jumping off point for Catamaran tours to the spectacular Napali Coast, a small naval facility, yacht outfitters and many light industries. It’s long industrial history has created a beach of cast-off bottle, windshield and other glass that has been ground down by decades of waves into a unique sort of sand. The “Glass Beach” is a popular stopping-off spot for tourists.

Those visitors often do not notice that, just across the parking lot, on a windswept point of land, is a picturesque and touching cemetery dating back to the 1800s. It is the last resting place for the workers of the McBryde Sugar Company plantation and their families, who lived in company work camps in the area. The company imported large numbers of contract workers, initially from Japan, and later China, the Philippines and even Europe.

By 1920, McBryde Sugar Company had approximately 1500 workers. Its company store and hospital served a number of work camps, one for each of the various ethnic groups making up the workforce. Workers lived in simple wood-framed dwellings, under sheet metal roofs, with bedrooms and a kitchen with a wood-burning stove. An outdoor shower, laundry and outhouses were shared in common.

With the transition to mechanization in the 1930s, the need for a large labour force for fields and mills disappeared. Most of the work camps were closed, and the cemetery was abandoned and forgotten. It become so overgrown by brush as to be almost invisible. Only the tireless efforts of local resident Debrah Davis commencing in 2013 have made the site accessible again.

This unveiling brought with it renewed interest in those at rest there. Some families from Asia and workers’ descendants still living in Hawaii have rediscovered a part of their heritage. This is presumably why several of the graves have restored or new markers, some not of the local red stone that underlies the cemetery and much of the island.

Conducting a little amateur archeo-geneology, I decided from the grave inscriptions (those in English – about half) that clearly, many workers brought with them or found wives, and raised families. I wondered what, if anything, their contracts said about that? Was that company policy to build a resident non-contract source of workers? Or did they initially feel that love and family would distract workers from their jobs?

In any case, life for the workers and their wives was often short. Deaths between ages 18 and 30 are particularly evident on the men’s headstones, due to workplace accidents, perhaps? Several women’s graves show deaths in their mid-20s, presumably from childbirth in some cases.

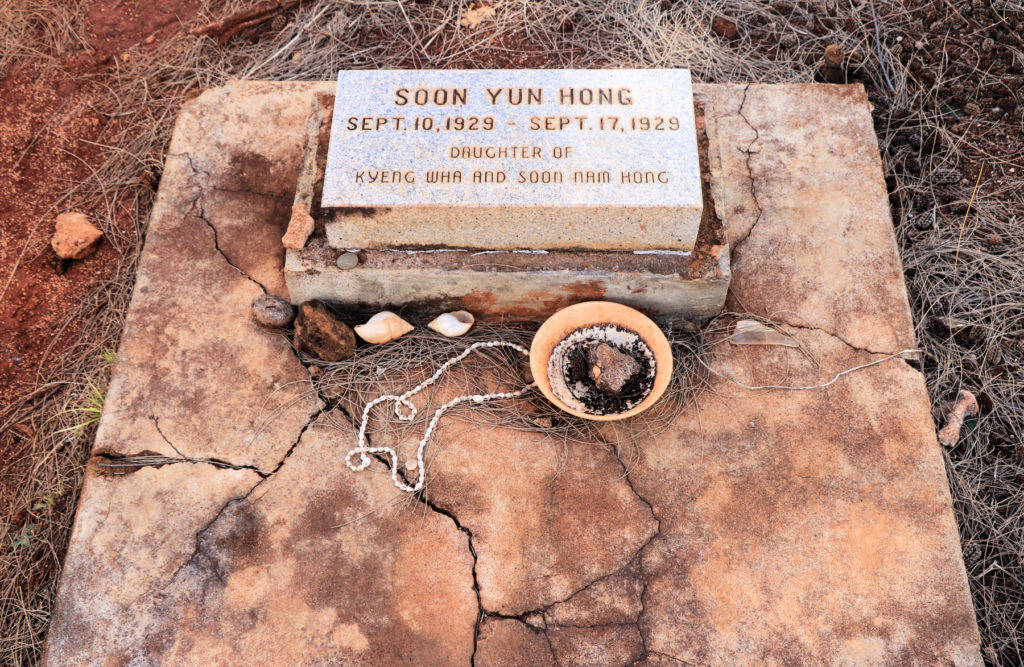

Children, too, often did not survive. One intensely sad memorial reads:

“Sun Yung Hon Sept 10 1929 – Sept 17 1929, Daughter of Kyeng Wha and Soon Nam Hong.”

The short-lived infant’s grave is among those recently restored. Who paid for that, I wonder? Was it the Chinese descendants of her mother or father, who discovered at last what had become of a lost ancestor said to have emigrated to America? Or did Sun Yung Hon have siblings, whose grand-children still live in Hawaii and decided to preserve the memory of a life too short, but cherished enough to acquire a formal grave? Someone clearly cares still; the headstone had upon it traditional Hawaiian grave offerings of shell beads, coral, sea-shells and a bowl for incense or candles.

Not all lives were short. It appears that if you managed to get past the hazards of work, disease and child-bearing, you could live to a ripe old age. A few graves celebrate men and women who reached ages past fifty. These tended to be larger than the rest, suggesting that a long life meant creating an extended family that could collectively afford a grander gravesite for its matriarch or patriarch.

I spent only 90 minutes at the McBryde cemetery. Still, it was among the most remarkable memories I brought back. A newspaper report indicated that Debrah Davis was having trouble attracting official or local sponsorship to maintain and restore the site. It is the sort of project that, if closer to home, attracts the support of organizations like the Workers’ History Museum. I wish her luck. It is a site well worth recognition and further investigation and research. The University of Hawaii, for example, still has the company’s personnel and payroll records. Could we learn from them more about the lives of the men and women who laboured in the surrounding fields, whose headstones survive to commemorate their existence?

Back in Ottawa, I did a little research and found that the McBryde enterprise is interesting in itself, showing how industry and agriculture and their workers are an integral part of the history of a region, or in this case, an island, and form the basis for its modern cultural makeup.

The company was founded in 1899 by entrepreneurs that bought out the original owner of much of the land under sugar cultivation in the area, Judge Duncan McBryde. Though named in his honour, it was the only connection between his family and the company. It absorbed at its founding several smaller sugar firms whose workers had already been providing burials at the cemetery for many years. They immediately built a new sugar mill which locals and workers rendered as “Numila”.

The McBryde company faced many challenges besides the need for labour. The best land on Kauai for sugarcane was also the driest, and massive steam-driven pumping systems for irrigation consumed a great deal of very expensive imported coal. So, the company built a reservoir in the mountainous far north of the island to feed a hydroelectric dam. Thus was born in 1905 the Kauai Electric Company which pumped water from a second artificial reservoir nearer the cane fields. In the same year the Kauai Railway Company started hauling the sugar product to Port Allen and from there to world markets. This has parallels in Ottawa, where the first hydroelectric plants were built by and for the pulp and paper industry, and the first commercial streetcar lines were established by the same entrepreneurs who first provided electricity to the city.

The Second World War caused a labour shortage and disrupted shipping for Kauai’s sugar producers. This proved the start of a long decline for the island’s main industry. In more recent decades, typhoons destroyed mills and sugarcane crops, and the acreage was converted to more robust and profitable coffee and macadamia crops. McBryde Sugar was officially wrapped up in 1996, but the corporate entity, now a major coffee producer, carries on. Its flagship store and museum are still located on a road, and area of the island, named “Numila”.

Click Here For The Genealogy Research Journal

Sources for this story include:

University of Hawaii: http://www2.hawaii.edu/~speccoll/p_mcbryde.html

The Kauai Travel Blog: https://www.kauaitravelblog.com/mcbryde-sugar-plantation-cemetery/

An item in TGI – The Garden Island Newspaper https://www.thegardenisland.com/2013/10/15/hawaii-news/resurrecting-the-cemetery/ and https://www.thegardenisland.com/2018/03/11/lifestyles/the-mcbryde-sugar-company-mill-at-numila/

The Kauai Coffee Company Website https://kauaicoffee.com/blog/sugar-cane-history-kauai-coffee/