The WHM image archivist has been assembling a collection of images not available elsewhere to become a unique record of the lives and workplaces of workers. While yet to be officially launched, we are featuring here a Gallery of some of the more interesting ones, and the stories behind them. In coming months, we will add more, so do check in from time to time.

If anyone viewing these images recalls having similar ones in family albums, perhaps of parents, grandparents or other relations at their workplaces, or any other scene depicting work, workers and workplaces, we would be happy to consider adding digital versions of them to our collection. While our focus is Ottawa and surrounding regions, images depicting work and workers elsewhere are also welcome. Direct your inquiries to images@workershistorymuseum.ca.

These die stamps, used to punch labels into metal or wood, were photographed in a workshop in the Domtar (former E B Eddy) Paper Mill in Ottawa-Gatineau, a lumber and paper-making center for 200 years until its closure in 2006-07. A team of volunteer photographers organized by the WHM spent 13 months making a thorough record of the closed plant before the property was redeveloped. The resultant 70,000 images and 36 hours of video are available to researchers. Photographer: Paul Harrison, WHM Image Archivist

This evocative image by WHM photographer Caje Rodriques depicts the simple, dignified monument in Ottawa’s Vincent Massey Park. Erected by the Canadian Labour Congress in 1987, it forms the centerpiece of an annual ceremony on 28 April, a National Day of Mourning for those killed or injured at their workplace.

Initially sponsored and celebrated by major Canadian national unions, the Day of Mourning has been an official national observance in Canada since 1990, and is also celebrarted in over 100 countries worldwide.

This monument stands a short distance from the Heron Road Bridge, whose collapse during construction in August 1966 took the lives of nine men and injured 60 others. For a dramatic description of that event, see this Ottawa Citizen account

The Workers’ History Museum is engaged in an effort to record photographically Eastern Ontario’s monuments and other sites reflecting workers’ history. One such is the Brockville railway tunnel, shown here. It has been re-opened to the public that can now stroll its 535-meter length, passing under several downtown streets as you do so, and enjoying a sound and light show at the same time. The tunnel was built to allow the Brockville and Ottawa Railway access to the waterfront. The tunnel took over six years to complete, going into service in 1860. Much of it was constructed by digging a trench from the surface, which was later covered over. Goods from ships docked at the waterfront would be transferred to trains, pass under downtown Brockville, and proceed north to Arnprior, Smiths Falls and Perth. Photographer: Paul Harrison, WHM Image Archivist

This workbench in Scanno, Italy, is covered with gold- and silversmithing tools. It was in use continuously from 1800 to 1975, in the hill town in the scenic Abruzzo region. The tools remain in occasional use today, and the di Rienzo family’s shop where the workbench is located still offers the traditional jewellery of Scanno and the Abruzzo region of Italy, much of it hand-crafted on site.

Images by Paul Harrison, added to the WHM collection with the kind permission of Armando Di Rienzo, Gold and Silversmith, Scanno, Italy.

This the Ottawa Electric Railway Company streetcar #664 operating on the Hull-Patrick Line in 1948. There are a surprising number of such images for this period available to collectors and archivists because photo hobbyists at the time set out to create a full set of images of all the streetcars (and later buses) in their city, much as coin and stamp collectors seek to acquire a complete set of each edition of a country’s stamps or coins.

Ottawa was served by streetcars from 1891 to 1959. For much of that time, they were operated not as a city service, but by a private company, the Ottawa Electric Railway Company. It was formed by two of Ottawa’s most remarkable entrepreneurs, Thomas Ahearn and Warren Soper. Their companies not only operated the streetcars, but also provided the electricity to the cars and the city’s electric lights, built the streetcars, which they marketed along with railway cars across North America, owned and operated Britannia park as Ottawa’s most important recreation arera (served, of course, by a streetcar line), and built military equipment in both world wars. At its peak in 1929, the OER had 90 km of track and employed over 300 drivers and conductors.

In 1948, the City of Ottawa formed its own Transportation Commission which took over the streetcar system (which by then included buses), the power plants, and Britannia property. Streetcar service ended on May 2, 1959 when Ottawa’s citizens lined the streets to watch one final parade of the cars through the city.

A dramatic image of the E B Eddy Paper Mill taken by a photographer determined to brave the intense cold of the winter of 2005. The complex was heated by steam produced in the company’s own generation facility, and piped to mills on both sides of the Ottawa River. When released, it quickly condensed into the white plumes that neatly frame the Parliament buildings just downriver. While most Canadians perceive Ottawa as a government town, it has a history as a center of manufacturing and pulp and paper industries going back 200 years. The E B Eddy mills, by then part of the Domtar empire, were closed in 2006-07. The photographer, Raymond Massé, has kindly donated the image to the WHM.

Photography as we know it was invented in the 1840s, but a practical method not involving complex and bulky chemicals on glass emerged in 1884 when George Eastman marketed “film” – a dry gel on paper – that could be developed in a studio dark room in simple, timed steps. The processes were easy to learn and required relatively little investment, so there was a rapid flourishing of photo studios worldwide. Ottawa was no exception.

One source* lists over 80 studios in Ottawa during the period 1868 – 1929. While a few, such as the William J Topley chain, became well-known and many examples of his studios’ work survives, most are known only through faded advertisements in period newspapers. Many appear to have existed only briefly, suggesting that it was a highly-competitive business, easy to launch, but difficult to achieve profit, not unlike the modern photography profession.

A formal studio portrait became a regular feature of various stages of family life, and were delivered to the customer as a “cabinet card” with the image on heavy stock cardboard about 108 by 165 mm (4 1⁄4 by 6 1⁄2 inches) in size, such as the one shown here. This was visible when displayed in a cabinet in a typical-sized parlour, hence the name. They are easily found in antique stores and provide often touching glimpses of people of the period.

This image bears on the back a logo of “Wallis – Photographer – Sparks Street – Ottawa” with the emblem of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, who was Canada’s 10th Governor General from 1911 – 1916. This implies – not necessarily truthfully – that the Duke was a patron of the Wallis studio. The inclusion of the ducal crest on this image strongly suggests Wallis studio still operated during the Duke’s term of office in Canada. This is curious, because while the Ottawa photographer listing cited above does indeed include Wallis studios, no entry appears after 1902. Did Wallis become so well-known that he did not need to advertise in the popular press? Or did another Wallis, perhaps a son, continue the business after 1910? The much lower-ranked couple depicted are described in a penciled notation on the back as “George Ferguson and wife Eliza Keys. George worked at Fallowfield and met Eliza there.” Fallowfield is today little more than a crossroads, but at the turn of the 20th century it was a bustling town with numerous small industries and services, and a stopping place for travelers en route to Ottawa. It is not surprising that George would have found work there and a social circle large enough to include an eligible young lady to woo.

This set of antique woodworking planes was arranged and photographed for archival purposes. They are part of a collection of wood-working tools in the Museum’s artefact collection, donated by the descendants of two lifelong woodworkers, Gus Hatfield (1916-1981) and Pat Sullivan (1903 -1988). Many of these tool assemblages were featured in our 2018 Calendar.

Photographed by Bob Acton, with arrangement advice by Paul Harrison.

The Museum is always happy to consider donations of artifacts and documents related to the history, work, lifestyle and union activism of Canadian, and especially Ottawa-area workers. If you have tools, documents or images you think may be of interest, please contact us at info@workershistorymuseum.ca.

Demolition of the old post office is seen underway in May-June 1938 on what was then called Connaught Place, later Confederation Square. Just out of sight on the left, the national war memorial was nearing completion and would be dedicated a year later. The concept was to have the War Memorial as a centerpiece in a grand, open plaza, so the old post office had to go quickly. It was demolished in just 8 weeks, allowing time to landscape the space where it has stood, and the rest of the plaza. A new post office was constructed at the same time and still stands at the northeast corner of Sparks Street, overlooking the war memorial. While a postal outlet is still in operation on the main floor, the rest of the building is occupied by offices of the Privy Council.

A year after this photograph was taken, on 21 May 1939, reigning King George VI, accompanied by Prime Minister MacKenzie King, dedicated the new war memorial “to Canada’s honoured dead” of past wars. Ironically, both he and the Prime Minister were even then certain that another war loomed in Europe, and that the memorial would soon commemorate the sacrifice of many more “honoured dead”.

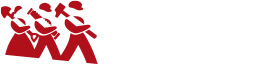

This massive container, one of three, is a “hydrapulper” at the former E B Eddy paper mill in Ottawa. Its accompanying installation schematic, dated January 1949, is also shown. The huge vat mixed wood pulp with the chemicals appropriate to the type of paper being produced on a given day. The schematic was found in the now-closed plant where, with the permission of the current owners, Windmill Corporation and Domtar, a Workers’ HIstory Museum team spent 13 months recording the facility prior to re-development.

Also nearby was the chemical laboratory where the mixture was carefully quality-controlled and product testing conducted. The buildings that contain them and, in times past, the massive paper machines they fed, were recently demolished to make way for condominiums. The E B Eddy mills operated at the Chaudière Falls in Ottawa for over 150 years, and employed about 2000 workers when it closed in 2006-07.

Photographer Paul Harrison

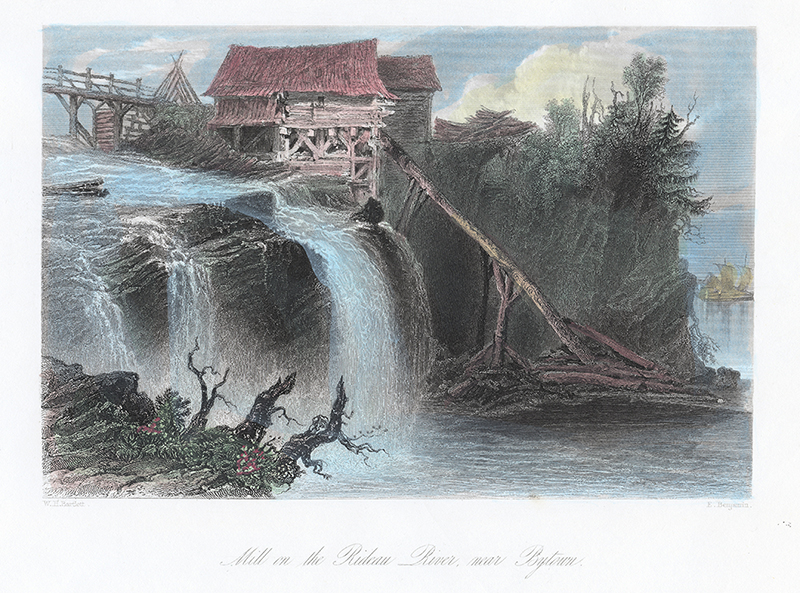

Before there were professional photographers, there were professional illustrators, who created accurate drawings of scenes for what today we would call coffee table books, as well as illustrations for travel and antiquarian books popular in middle-class society of the 1800s. One such was William Henry Bartlett. He was apprenticed in England in 1822 to architect and antiquarian John Britton, who early recognized the young Bartlett’s talents as an illustrator. Working on assignment to Britton and numerous other publishers, Bartlett had a successful career that saw him travel widely, including to North America. While he never achieved recognition as an artist, William Bartlett’s hundreds of drawings not only graced the books of his employers but became popular as individual wall prints. They remain in print to this day, often fetching substantial prices.

This one, measuring 12 x 18 cm, was found in an antique shop and purchased for much less than its actual value. It was acquired by the Museum because it is one of the earliest depictions, dated 1842, of a sawmill at Rideau Falls. Rideau Falls, like all, falls in the region, attracted lumber and later paper mills that needed hydraulic power to drive saw blades. While familiar to present-day inhabitants of Ottawa as a scenic park and natural wonder, Rideau Falls remained an industrial site until after the Second World War when it was acquired by the National Capital Commission. The Museum has a number of images of the Falls later in its industrial career. Stay tuned!

Photographer Paul Harrison