By Paul Harrison

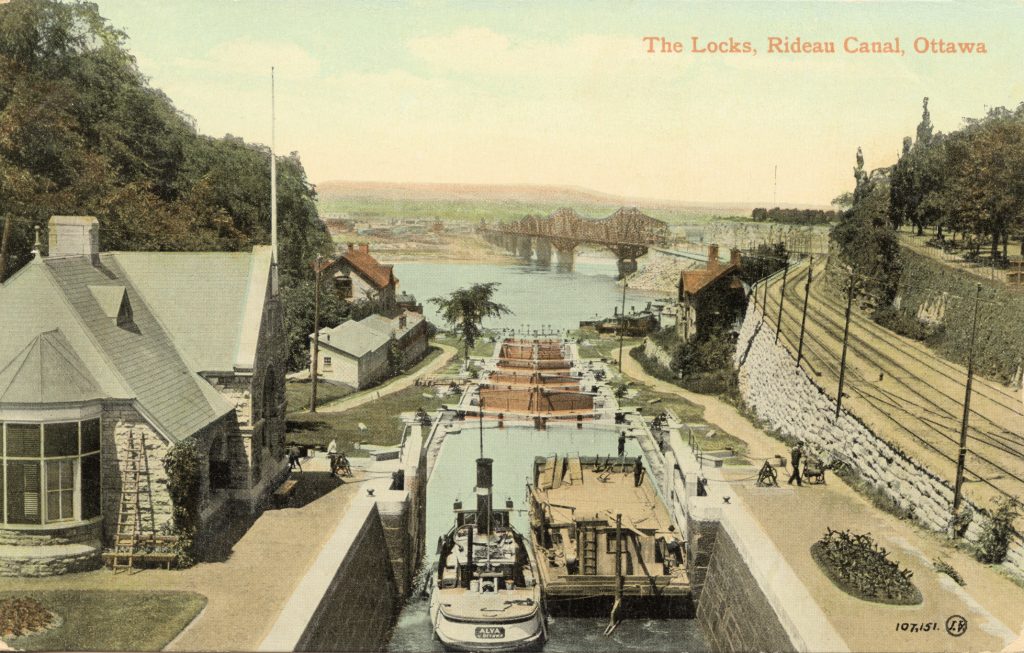

Alva with barge in locks 1905; Workers’ History Museum Image Collection PC0112

Among the WHM’s image collection items are postcards of the Rideau Canal locks below Parliament Hill, a popular vista – then as now – for visitors to the capital. Unlike most, however, one – dated to about 1905 – shows the very unaesthetic workaday world of the canal; a tug lashed to a barge, downbound. The name of the tug is visible: the Alva. A check of the registries of the time reveal only that she was originally named the Minnie Bell. I set out to find out more about her. Most of the eventful history of the vessel related below comes, unless otherwise noted, from the Ottawa newspapers indexed and searchable on the marvellous Newspapers.com website.

The bare details of her history are found in the amazing Maritime History of the Great Lakes website [01]. Its entry for the Minnie Bell shows that she was screw-propelled, steam-powered, constructed in Ottawa in 1887, massed 22 gross tons, and was 50 feet long and 13 abeam. The dimensions were a standard for Rideau Canal vessels, being the near-maximum dimensions of the locks themselves. [02]

HEAVY DUTY!

We tend to think of tugs today as engaged mostly in gently nudging very large vessels. Minnie Bell and her cousins on the canal at Ottawa were, in contrast, long-distance heavy cargo-haulers. As recorded in the daily Shipping News entries of Ottawa newspapers during for the period 1893 – 97 she made regular trips from Ottawa to Oswego New York towing up to four barges of lumber, possibly from the J.R. Booth sawmills, often returning from there with sand from Lake Champlain for Smiths Falls.

Why cart sand such long distances? Well, it was no ordinary sand. At the time, Smiths Falls was home to the Frost & Wood Foundry & Agricultural Works [03] producing agricultural implements. This involved casting: pouring liquid metal into moulds of shaped and compacted sand. The metal solidified into tools that needed only to be given a final polish before sale. The sand from the Lake Champlain region was perfect for this purpose, and accordingly called “foundry sand”. So specific is this sort of sand for casting [04] that it was worth the cost of commercial shipping from Lake Champlain through the Erie and Oswego canals, across Lake Ontario to Kingston, and up the Rideau Canal to Smiths Falls.

Output of the Frost & Wood mills, the two cheese factories in Manotick, and the many other industries in towns all along the canal, were in turn shipped out by barge, with destinations as far away as Montreal and (back through the Oswego and Erie canals) even to New York. The barges towed on such long-distance trips were the same size as the tug itself. So, at each set of locks, the barges, which were unpowered, had to be manually drawn through one-by-one, and re-attached to their tug at the other end. [05] Less-bulky retail goods for stores in towns long the Rideau Canal – sugar, flour and hardware – were likely to arrive in the holds of a considerable fleet of relatively luxurious passenger steamers that also plied the canal between Ottawa and Kingston.

All to say, Ottawa, with its wide freighter basins within sight of Parliament Hill and its maritime construction and maintenance facilities, was a very busy place and a key shipment terminus. The Citizen reported in December 1904 that “At the canal basin and the foot of the canal locks are collected about as cosmopolitan a lot of river bottoms as could be found anywhere, ranging from the heavy-bodied freighter to the pugnacious looking little tug and trimly cut pleasure craft, not to say anything of the fleet of blue-bottomed lumber and coal dredging outfits that seek their harvest in the sands at the river bottom.” (Oh, that modern newspapers were so erudite and descriptive!)

HAZARDS

Such operations were not without their hazards. Minnie Bell was frequently in drydock for repairs. During the 1893 season she managed to break three propellers, each requiring a replacement. Groundings were not uncommon, and the traffic levels on the canal in its heyday presented their own challenges. In June 1888, the Ottawa Daily Citizen reported that the Minnie Bell managed to get the barge it was towing and its load of lumber destined for the Canadian Atlantic Railway wedged “between the steamer Harry Bate of the Merchants’ Despatch Line and the barge C. F. Hammond, in the Rideau Canal south of Sappers’ Bridge”.

One of the incident reports also give us a clue to the manning of the vessel, which it appears may have been something of a family affair. References over the years to both Minnie Bell and Alva refer to it as owned by Captain Henry E. Shaver from 1895 to at least 1904. The Citizen reported in July 1901 that the tug Alva’s engineer had suffered an injury when the tug, having run aground, engaged another vessel to pull her free. The rope between them slackened and abruptly tightened, striking the engineer and throwing him across the vessel. The name of the engineer was Albert Shaver. The newspaper report did not note a relationship with the captain and owner, but genealogical research confirms that he was in fact Captain Shaver’s son, Samuel Albert, a marine engineer by profession.

True to the journalistic tradition of the times, Mr. Shaver’s injuries were described with some relish. In addition to a broken left arm, “…his beauty was badly disfigured. The left side of his face was a mass of scratches and above the left temple an ugly gash gaped and that with a broken nose made him look as if he had been the worst used man in a Donnybrook fair.”

DANGER FROM ABOVE

While clearly operating a tug was not without such routine perils, even the most boastful of their captains are unlikely to list among the dangers a railroad locomotive descending onto the deck. According to the Ottawa Journal, on the morning of 12 August 1891, this experience was only narrowly missed by the Minnie Bell. At the time, the busy rail yard on the east side of the canal, where the Queensway crosses it today, featured a swing bridge for trains to traverse the canal. That morning, a locomotive engineer had left his train to get orders at the office. The conductor and brakeman were both also off the train and later claimed to be unaware that only the fireman, Fred Page, was still in the cab of the locomotive. They signalled the locomotive to back onto a siding to add a dozen more cars to the four already attached. Fred confidently pulled forward to draw his four cars beyond the switch point, so he could back onto the siding. Now, a locomotive, tender and four cars needed a considerable length of track going forward to clear the siding, which meant partially crossing the swing bridge. This Fred set out to do, assuming the bridge was still in place over the canal.

It wasn’t, because Minnie Bell was underway northbound up the canal, and had whistled its approach to the bridgeman, named Wallace. He dutifully deployed the semaphore to stop all trains, and swung the bridge lengthwise down the center of the canal so Minnie Bell could pass. Wallace then saw the engine approaching, the driver with his back turned, the locomotive moving too fast to stop, and Minnie Bell almost at the gap. He shouted, but could not be heard. The Minnie Bell too saw the danger and its frantic whistle blast finally alerted Page, who applied the brakes almost, but not quite, in time.

It is hard to imagine the thoughts of the crew of the Minnie Bell as, from less than 100 feet away, they watched the locomotive, its tender, and the first of the cars roll off the tracks where the bridge had been, and plunge headlong into the canal. According to the Ottawa Journal account “The engine went head first and turned completely over, striking the water on her back. There was a great splash… and the live red hot coals falling out of the furnace struck the water with a loud hissing noise, causing a cloud of steam to fly up. The tender followed the engine, landing on top of it. The first freight car followed, and when about half over it broke in half, one half remaining on the track, the other falling into the water.”

Incredibly, the bridge was undamaged, canal traffic (including Minnie Bell) were able to pass on the other side of the canal from the wreckage, and the locomotive was raised, refurbished, and returned to service. The worst damage was to fireman Fred Page. He had jumped clear and was physically unharmed, but was quickly blamed for the accident. The yard superintendent told the press that Page did not have authority to run the locomotive. However, he went on to describe what Page did wrong, phrased in a way that made clear that firemen, presumably including Page, often finished making up the train while the engineer and conductor where in the station picking up their orders. [06]

FIRE!

Minnie Bell’s trials were not over. In the early hours of 29 November 1900, a railroad watchman reported to the Number 8 Fire Station that she was on fire at her berth near the Laurier (then Maria Street) Bridge. (That late in the season, it is likely that Minnie Bell was laid up for the winter.) The Brigade responded and, “after laying 800 feet of hose and doing considerable fighting, the blaze was extinguished,” according to the Ottawa Citizen. The damage was confined to the upper works of the tug, and was covered by insurance. The Shaver family not only repaired the damage (presumably in the capable shipyards then in Ottawa) but seem to have added unspecified upgrades, for the re-registration of the vessel shows her with the same dimensions as when launched, but now massing 27 tons, five more than when launched. [07] This may have been due to the installation of a new boiler over the winter of 1901-02.

FAMILY TRAGEDY

Another important change occurred over that winter. The re-registration of the rebuilt tug was apparently an opportunity to give her a new name, and the “Minnie Bell” commenced the 1902 season as the “Alva”. This was almost certainly in memory of the Shaver’s son, “Alvy”, who tragically drowned in May, 1895, at age 19, after falling into the canal basin near the Sapper’s Bridge. Witnesses say he made no effort to keep himself afloat, and the family noted that he was prone to fits, one of which was presumed responsible for his falling in and failure to save himself.

NEW OWNERS EXPERIENCE AN UPSET

The investment in upgrades after the fire, and the renaming of the tug after a lost child, clearly suggest that at that point the Shavers had faith in the prospects of the boat. Soon, however, the family connection was to come to an end.

Alva still belonged to Henry Shaver at the end of the 1904 season, but by 1910, she had passed into the hands of Messrs. St. Jean and Cousineau. Its eventful career continued with an accident that blocked the locks below Parliament Hill while engaged in the relatively humble work of moving a sand scow. She must have looked, while locking down, much as she appears in the postcard above that inspired this article. Lashed to the scow, the Alva was preparing to exit into the Ottawa River from the last lock when the scow abruptly turned turtle. Alva was very nearly dragged under with it, but the securing lines fortunately snapped. The four-man crew – Captain St. Jean (one of the owners), his wife, a fireman, and an engineer – “jumped for their lives to the locks walls” the Citizen reported, and were unhurt. (It is interesting that The Citizen included the captain’s wife among the “crew of four”. If formally a crew member, it would be interesting to know what her duties entailed. Was she a cook or something similarly domestic, or did she participate in the tug’s operations?)

The sand was for delivery to the City, to whom the owners were contracted to supply it. Perhaps to protect that contract, Alva’s owner, M. Cousineau, blamed the incident on the carelessness of the crew who, he told The Citizen, had failed to pump out the scow’s hold, known to be leaky, before entering the locks. The result was that the saturated sand became a semi-liquid slurry that shifted to one side of the scow and rolled it over. While his criticism of the crew presumably was not intended to include his co-owner and captain, one wonders why it was not Captain St. Jean’s responsibility to assure such essential tasks as the pumping had been carried out.

The news report added that the scow, while repairable, could not be removed from the lock until the sand had been washed out through the lock’s sluice gates. The owners would bear the cost of that, and needed to replace a special sand pump on the scow valued at $2,000. This incident and consequent expense seems to have dampened the entreprenurial spirit of the new owners. Government records show that one Reverend Cousineau of Sarsfield sold the Alva to the Ministry of Public Works the following June for the sum of $3,500. [08]

END OF THE ALVA AND CANAL SHIPPING

A characteristic of Rideau Canal and Ottawa River navigation – and its inherent commercial vulnerability – was its seasonal nature. Canadian winters meant that ships and sailors were off duty from December through May. Though the shipyards, drydocks and basins of Ottawa were not idle – new ships were built and existing ones repaired and upgraded over the winter – the income which sustained them disappeared for five months a year. Railroads serving canal communities had no such limitation, and had been making inroads into canal shipments since the 1850s. This process reached a tipping point during World War I, when a number of railways expanded along the Kingston-Ottawa corridor, and amalgamated in 1919 under government fiat to become the Canadian National Railway. The canal seems to have become, in an astonishingly short time, commercially redundant. [09] The two shipping basins located on the east and west sides of the canal just south of what is now Confederation Square were filled in by 1927. [10]

The last record I could find of the Alva shows her registered to the Dominion Government in 1917 and 1921 [11] as the Public Works Department Dredge Tug Alva[12]. Below is a photograph of her dated 1917, tucked in among her new work companions. In the foreground is a barge that the dredge (behind, labelled Public Works Dredge number 103) would fill with mud lifted from the river or canal bottom. It would have been the responsibility of the Alva to move them about to do their work.

It is ironic that the construction, and disappearance from history 35 years later, of the Minnie Bell / Alva coincided almost exactly with the rise and extinction of the shipping industry and network in which she had been a fixture. Steam whistles were still to be heard along the Rideau Canal, but they were from passing trains, not canal steamers, whose day had passed.

[ 01 ] http://www.MaritimeHistoryOfTheGreatLakes.ca/

[ 02 ] Ken W. Watson http://www.rideau-info.com/canal/tales/failed-gates.html

[ 03 ] http://www.vintagemachinery.org/mfgindex/detail.aspx?id=2012

[ 04 ] https://www.afsinc.org/introduction-foundry-sand Foundry sand remains important to this day for the casting process, and fresh sources are difficult to find. Much effort is going into recovering sand cast-off from production decades ago, so it can be re-used.

[ 05 ] Ken W. Watson http://www.rideau-info.com/canal/tales/failed-gates.html

[ 06 ] Numerous news reports, summarized in Colin Churcher’s Railway Pages https://churcher.crcml.org/Articles/Article2004_5.html ] Mr. Church is confident that Page and his fellow firemen routinely moved the locomotives about the yard to make up the train while everyone else was doing paperwork in the office.

[ 07 ] http://www.MaritimeHistoryOfTheGreatLakes.ca/

[ 08 ] Privy Council Office Order-in-Council, LAC Item 301503

[ 09 ] Reminiscence by Kenneth Parks in Ottawa Journal 14 September 1946

[ 10 ] James Powell in Ottawa City News Nov 16, 2020

[ 11 ] http://www.MaritimeHistoryOfTheGreatLakes.ca/

[ 12 ] LAC Item ID number: 3271270